“There is a global disability inequality crisis. And it can’t be fixed by governments and charities alone. It needs the most powerful force on the planet: business.”

— Caroline Casey, Founder, the Valuable 500

Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Accessibility (DEIA) is a topic advocates talk about daily. So much work is happening and yet simultaneously so much work remains. Oftentimes, I think of advocacy the way I think of a book jacket. The material might be the same but different covers may resonate with each member of your audience.

As the World Economic Forum kicks off in Davos this week, I thought it was important to highlight the Valuable 500 Initiative—the largest global network of chief executives committed to disability inclusion. Launched in 2019, the initiative aims to “set a new global standard for workplace equality and disability inclusion by engaging 500 private sector corporations to be the tipping point for change and to unlock the business, social and economic value of the 1.3 billion people living with disabilities across the world.”

Some of the world’s biggest companies including Apple, Microsoft, Google, Sony, and Verizon are among its participants.

Although 90% of companies claim to prioritize diversity, only 4% of businesses are focused on making offerings inclusive of disability according to the World Economic Forum.

A May 2022 report published by the Valuable 500 also found that:

• 33% companies surveyed have not developed or begun to implement a digital focus on accessibility

• 29% of companies have a targeted network of disabled consumers or stakeholders.

The cost of excluding people with disabilities represents up to 7% of GDP in some countries. With 28% higher revenue, double net income, 30% higher profit margins, and strong next generation talent acquisition and retention, a disability-inclusive business strategy promises a significant return on investment.

On the federal level, data on inclusion efforts tells a similarly disheartening story. A newly released report by the EEOC found that persons with disabilities remain heavily underrepresented in leadership positions; 10.7% of disabled employees are in positions of leadership vs 16.4% for those without. Further, the report noted that people with disabilities were 53% more likely to involuntarily leave federal service than persons without disabilities.

Clearly, both privately and publicly, a lot of DEIA work remains. These disconnects in the data further support the need for advocacy around not only things like Global Accessibility Awareness Day, but also an increase in disability representation to effectively close these gaps.

Let disabled people not simply have a seat at the table, but a voice in the conversation. Your company will be better off for it.

Global Accessibility Awareness Day

"The truth of the matter is, Netflix Director of Product Accessibility Heather Dowdy explained, the disability community “has been here all along.” As such, it makes sense to want to normalize and tell their stories. Indeed, the pandemic has only reemphasized the importance of accessibility and assistive technologies."

Forbes, Steven Aquino

-

Today we celebrate Global Accessibility Awareness Day, highlighting the advances making technology and entertainment more accessible to the disability community. Oftentimes, seen as an afterthought, these enhancements are vital to ensuring disabled people can participate equitably as consumers of entertainment as well as fully leverage a company’s complete product line readily and with full confidence their needs will be met.

The disability community accounts for 20% of the global population, the largest underserved minority. When you consider accessibility for one, you enable it for all. So many of the tools and technologies in wide use today were initially developed for disabled people, and yet are seen as ubiquitous today. Think captions, speech to text, or screen adjustments on mobile devices.

In recent days companies like Apple, and Microsoft have rolled out enhancements to their product lines aimed at people with disabilities. Apple, for example unveiled Door Detection, helping those with vision impairments more easily navigate their surroundings. Additionally, they’ve improved functionality of the Apple Watch allowing it to be controlled through the iPhone; a larger screen with more real estate that also allows users the benefit of assistive technology already present within iOS— features like voiceover and magnification— not yet independently available on Apple watch.

For its part, Microsoft announced Thursday in a company blog post recent improvements included in Windows 11 that aim to make its OS more accessible, including Live Captions and new natural voices for users of screen readers. Last week at its annual Microsoft Accessibility Summit, a slew of adaptive technology for computing and gaming was also unveiled. Additionally, Microsoft touted its recruitment efforts to improve disability representation within the company.

A new study from Microsoft Education found that 84% of teachers say it’s impossible to achieve equity in education without accessible learning tools. And 87% agree that accessible technology can help not only level the playing field for students with disabilities but also generate insights that help teachers better understand and support all their students.

Accessibility benefits everyone. While companies like Netflix, Apple, and Microsoft are to be applauded for their progress, they represent merely a step forward in equity. We must continue to push all companies, regardless of overall size, or market share to fully embrace equality for all. To that end, I look forward to the day when Global Accessibility Awareness Day ceases to exist and it fades into the background.

Madison Cawthorn

The disability community talks frequently about how representation matters, and it does, especially in Congress where that representation can lead to better lives for disabled people. Senator Tammy Duckworth of Illinois is a perfect example of the positive representation we need more of, routinely uplifting our community and showing what is possible through advocacy.

The flip side is recently unseated Representative Madison Cawthorn (NC 11) who is the worst thing to happen to disability representation since the rise of toxic positivity. Not only did his openly ableist views harm the disability rights movement, he actively found ways to misrepresent what it looks like to move through the world as a disabled person.

When we say representation matters, it does. Madison Cawthorn's re-election loss however is a positive step forward for disability rights.

Finally, congratulations to my friend Kristen Parisi whose reporting on Representative Cawthorn was recently featured on Jon Oliver's Last Week Tonight on HBO Max.

Over 3.5 Billion People Will Need Assistive Products by 2050: Report

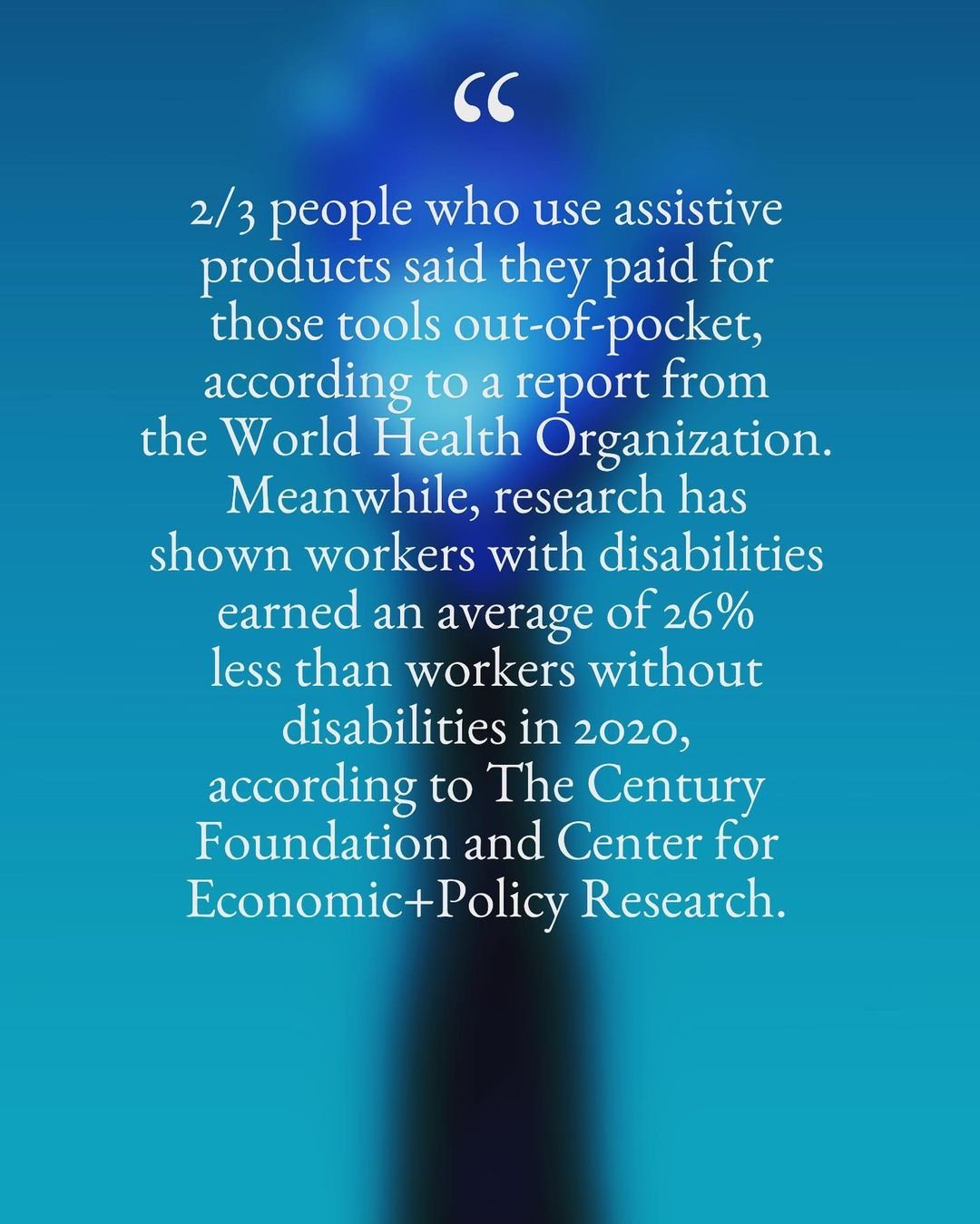

About two in three people who use assistive products said they paid for those tools out-of-pocket, according to a report from the World Health Organization. Meanwhile, research has shown workers with disabilities earned an average of 26 percent less than workers without disabilities in 2020, according to The Century Foundation and Center for Economic and Policy Research.

While some assistive tools are easily available, Maria Town, the president and CEO of AAPD Foundation said more "specialized" products can be "very costly," even if the individual in need has public or private health insurance.

Meghan Roos, Newsweek

I count myself among the 2.5 billion people who currently use assistive technology daily. Often, this is technology paid for out of my own pocket.

My wheelchair, leverages assistive technology in the form of power assist wheels. This technology enables me to move more freely and easily through different terrain without putting undue stress on my body in numerous ways; especially while working with Canine Companions® Pico as we navigate a major city with hills and distinct types of terrain. While insurance did cover some of this, a significant percentage came out-of-pocket. Without this technology I would not be able to navigate my life safely and easily. It has provided a freedom and flexibility that I would otherwise not have.

For years, I struggled with typing; causing strain and stress on my hands, fingers, and even eyesight. While I can effectively use voice dictation today and can attest to how much it has streamlined my workflow and saved me undue physical stress, the startup costs were innumerable.

For many people with disabilities, assistive technology is not a luxury, it is not a “nice to have,” nor is it something to ogle over and think about how cool it would be if you had it. It is what enables us to participate freely and easily in society that is not built with us in mind. We use this technology to level the playing field. However, it can and does often come at significant cost. Colloquially referred to within the disability community as the “Crip Tax,” it is the cost-of-living increase as a consequence of living life as a disabled person.

That is just one of the many reasons why equal wages are so important for everybody. Disabled people earn seventy-four cents on the dollar compared to our nondisabled colleagues. This is why, in every industry, every profession, and every company, representation matters. Disabled people need support from leadership not only so we can thrive at work with a supportive team that understands and appreciates our needs for assistive technology, but further so we can advance our careers on-par with our nondisabled colleagues and close the wage gap.

For us it is the difference between inclusion and exclusion, feeling seen, or feeling ostracized. Feeling validated or cast aside.

Over 3.5 Billion People Will Need Assistive Products by 2050: Report

Some Minority Workers, Tired of Workplace Slights, Say They Prefer Staying Remote

“People with disabilities have been left out of civic life for so long,” Carol Glazer, president of the National Organization on Disability says, “If we don’t see them in our schools, in our communities, in our workplaces, it only reinforces a lack of understanding and the implicit bias that leads to microaggressions.”

Alex Janin, The Wall Street Journal

As companies encourage a return to the office, it is important to remember that people with disabilities are at risk for being left out of the conversation. Many are still unable to safely engage in an office environment for medical reasons. The pandemic helped normalize work from home protocols and accommodations which were previously a struggle. Now, with those same accommodations seemingly rolling backward in favor of a return to “normalcy” many are having to choose between their health and safety and workplace visibility, effectively risking becoming second-class citizens in their own jobs.

There have been numerous times in my own career where an office environment was not always the most welcoming. I’ve often dealt with disparaging comments, micro-aggressions, and the all too often unsolicited advice/commentary that accompanies being disabled. Non-disabled colleagues often feel they have a right to not only to our medical history but to freely dispense advice about how to handle it. It is not only demeaning, but presumptuous, and extremely harmful. As a near daily occurrence, this can be exhausting. Most non-disabled folks wouldn’t think twice about preserving the privacy around most other discussions concerning health, yet disability seems to be its own designated category, unworthy of such discretion and privacy.

An office environment certainly does have its place and benefits when it comes to fostering collaboration. I am all for those things and support them when they can be done safely for all. But we are not there yet. We have also demonstrated over the course of the pandemic that many disabled employees benefit from accommodations and that no workplace hardship is created in doing so.

We should not be penalizing anybody (directly or otherwise) who chooses to work from home for the safety of their own mental and physical health.

Some Minority Workers, Tired of Workplace Slights, Say They Prefer Staying Remote

Disability Bias in AI Hiring Tools Targeted in US Guidance

As many as 83% of employers, and as many as 90% among Fortune 500 companies, are using some form of automated tools to screen or rank candidates for hiring, according to EEOC’s Charlotte Burrows.

-Bloomberg Law

With the rise of AI tools in recruiting, new guidance issued by both EEOC and U.S. Department of Justice is welcome news. Disability advocates have long known that while these tools can be useful for the employer, they can raise questions around bias that violate the ADA, including the use of personality tests with non-job specific questions, camera sensors, or timed tasks that don’t easily allow for reasonable accommodation.

This guidance also comes after U.S. Department of Commerce appointed 27 experts last April to the National AI Advisory Comittee.

The disability community already faces tremendous hurdles in hiring discrimination, in large part due to employers outdated views on what people with various disabilities bring to the table.

While AI can be a useful tool, and can certainly provide valuable insight, the hiring process needs more human connection and understanding across the board, not less, especially around disabled candidates.

New PSA Urges More Disability Visibility and Representation in Hollywood

“A [2021] report on the television writing from the Think Tank for Inclusion and Equity found that 93% of disabled writers surveyed said they were the only disabled person on staff, and 97% of writing rooms had no upper-level disabled writers.”

-Marc Malkin Variety

Think about that for a moment. Disabled people are massively underrepresented in entertainment. And we are as diverse as we are numerous, accounting for 20% of the global population. Over the last few years disabled people have slowly begun to see themselves in newer series, movies, and television.

While representation has certainly improved, all too often it’s done as a trope, or an act of tokenism that actually causes more harm than good. That’s why diversity in writing rooms and elsewhere in Hollywood is as vital as inclusion, equity, and accessibility itself. Each of these pieces work together and can not stand alone. We need not just representation of disability, but we need it across the spectrum to account for the depth, breadth, and power of the disability experience.

Thank you to Inevitable Foundation for your important work.

New PSA Urges More Disability Visibility and Representation in Hollywood

When Your Wheelchair is Your Legs: Holding Airlines Accountable For Broken Mobility Equipment

Travel these days gives me a bit more anxiety than it used to. It’s never easy, as I wrote about years ago, and a lot has changed. There’s my usual luggage, and my service dog, Pico. He is truly a joy to fly with as he rests at my feet and naps for the entire flight. There’s my custom-fit wheelchair with power-assist wheels, which took 18 months to obtain through insurance and still left me with several thousand dollars in out-of-pocket costs. Expensive? Sure. However, it’s a small price to pay for independence. So understandably, when I travel, there’s added stress when it comes to the treatment of my wheels by the airline. There are things we can do as wheelchair users to reduce the likelihood of damage, but as with anything in life, there are no guarantees. Traveling is especially stressful for wheelchair users. It’s why many of us avoid flying altogether.

As a wheelchair user, I’m entrusting an airline with the very thing that enables me to move freely throughout my day. Once I’m at the gate, I hope all my carefully articulated instructions are followed and that my chair is handled appropriately. I know some people who are nervous flyers. If they are religious, some will cross themselves to ensure a safe landing. The entire time I’m flying I’m wondering, “Will my ‘legs’ work when we land?” There isn’t enough in-flight entertainment to quell that fear.

When disability advocate and writer Kristen Parisi shared with me her tale of airline travel hell, I was saddened but not surprised. “We landed, and they didn’t know where my chair was,” she recalls. “There was no apology, no acknowledgement of how I must be feeling in this moment. They were more focused on getting me off the plane so the crew could go home. Airlines don’t care. They treat our chairs like they are pieces of luggage. Those are my limbs. I need them to survive and they treat it like trash.”

Parisi reflected that disabled people “are constantly forced to be advocates because society would rather just brush us off and not just deal with it. On the days when you’re just trying to have a vacation you still have to be a constant advocate for yourself.”

While the airline did eventually reunite Parisi with her chair after a two hour delay, data shows it’s a far too common occurrence for wheelchair users. Airlines don’t have the greatest track record with mobility equipment. The only reason we knew this is thanks to Senator Duckworth’s own experience, leading to legislation requiring airlines to report on the frequency of these incidents. (This is yet another reason why representation of disability matters, especially in Congress.)

From January to March 2021, Delta Air Lines handled 15,547 wheelchairs and scooters and reportedly mishandled 103 of those, according to the Air Travel Consumer report. Major airlines combined mishandled 712 or 1.19 percent during that same period, which roughly equates to 23 daily instances where a wheelchair user’s mobility equipment sustained damage. That number may seem small, but it’s still too many. If that many animals were dying as a result of negligence there would be an uproar.

Imagine the airline breaking your legs and saying, “We’re sorry. In the meantime, let’s send you to the hospital and we can fight over the bill later!” That’s essentially what happens when a wheelchair is lost or damaged. It’s not supposed to be that hard, but it is. They’re required by law to cover the cost of damage, repair, or replacement but it’s never that simple in practice.

Our mobility equipment is as unique as we are. Rentals aren’t always feasible and repairs take days, weeks, or months. Suddenly that trip you had planned isn’t happening and you’re stuck in a hotel room unable to move. It’s also likely that airlines are underreporting the actual amount of damage that occurs. The process of filing the multiple reports and providing documentation with persistent follow up can be exhausting, and the last thing any wheelchair user wants on top of damaged equipment is added stress. If your legs are broken, your first thought is dealing with the pain, not bureaucracy. When overwhelm kicks in and you’ve got limited time to follow a regimented process it can be anxiety producing, and with an inability to move, literally paralyzing.

Travel has never been easy for anyone, even prior to the pandemic. As we work to establish our new normal, new stressors are par for the course as we learn to navigate them. There is a lot about the future of travel that remains uncertain. One thing remains clear, however. As thoughts about travel begin to reenter the minds of travelers with mobility equipment, the anxiety that comes with our travel isn’t going anywhere. We need to continue raising awareness, making noise, and holding airlines accountable for their mishandling of our equipment. Travel can bring with it tremendous freedom and joy, provided that nobody takes our ‘legs’ out from under us when we land, but we still have a long way to go.

The Pandemic Created A Systemic Shift For Disability Rights and Accessible Space, Even If It Was Accidental

For the past 18 months or so during the pandemic, time stood somewhat still. Normal routines shifted or changed while still others fell off entirely. One that I missed deeply was my daily Starbucks run. Yes, they quickly adapted and offered drive up or curbside options, but it wasn’t until recently that I began slowly reemerging from isolation, back to Starbucks, and into the newly established normal.

I admit my anxiety about reemergence is high. I routinely find myself asking what a post-pandemic world will look like. Will the lessons surrounding the normalization of telework remain? What about telehealth and virtual appointments? Will disabled people who were shamed for using grocery delivery or reliance on food delivery apps finally feel free of judgement since they’ve now become commonplace? And what will going out into the world look and feel like as a wheelchair user with a service dog in public space? Everything feels so uncertain.

On my daily walk with my service dog, Sir Pico, I passed my local Starbucks and heard the familiar Siren song calling to me. “Go in. It’s been 18 months. Go in. You’re vaccinated. You’re masked. It’s okay. You deserve it. Maybe grab some avocado toast while you’re at it, you entitled millennial.” (My inner critic really needs to shut up.) It was part reassuring myself, and part feeling like my addiction grabbed me full-on by the shoulders and was shoving me toward the door.

I went in. From a disability perspective, what I saw was glorious. The Choir of Heavenly Angels sang in my head. OK, so it wasn’t that dramatic, but what I saw was open space and inclusive design that didn’t exist prior to the pandemic. Social distancing meant no narrow rope lines with customers standing shoulder-to-shoulder. The tables that once presented themselves like a navigational maze with potential death traps not dissimilar to the game Frogger, were gone. And customers weren’t packed wall-to-wall in every corner waiting for their drinks to be made while I, at my lowered height uttered “Excuse me, sorry about that.” I no longer had to navigate between random display items—constant reminders that the world is seldom built with disabled people in mind.

Instead, there was openness. I rolled in, and for the first time entered a public space that I felt gave me room to breathe. I had the ability to unapologetically be myself, to exist, and not feel like I took up too much space or was somehow unwelcome just by virtue of being me. I grabbed my drink which I had preordered on the app, thanked the barista, turned around, wheeled outside, and sat at the table contently sipping my Mocha Frappuccino, having felt seen for the first time in a long while as a disabled person.

If this seems like a simple moment to you, or perhaps like I’m getting too excited about an everyday event, that’s because I am. Not because I went outside and lived my life or because I’m vaccinated and the world is slowly opening. It’s because the pandemic has forced us all—especially businesses—to redefine what “normal” truly looks like. Prior to the pandemic, the disability community was routinely told that what we needed was “special,” or costs too much, or couldn’t be done because it created an organizational burden. But the pandemic proved all those obstacles were accepted simply because non-disabled people hadn’t yet felt the imperative to act beyond their own self-interest. For far too long the disability community felt excluded in spaces simply because they weren’t built for us. COVID thrusted upon the non-disabled a new lens through which to see the world, getting their attention in a way our screaming, yelling, and pleading could not; because they finally, for once, saw themselves in us.

As a disabled man, I could not be more elated by the possibility that open space is the new normal. As short as our collective memories may be, I’m hopeful that at least this one lesson about accessible spaces sticks. The disabled community will continue to fight for more access and more inclusivity, but for right now, in this moment, I’m going to take the win for this unintended result of COVID. I wish it hadn’t taken a pandemic to get here, but I’m ready to enjoy the wide open space.

Using Rideshare Services Isn’t Easy When You Have a Service Animal. That Needs to Change.

This post originally appeared on the Rooted In Rights blog.

Not that I condone fascism, or any -ism for that matter. -Ism's in my opinion are not good. A person should not believe in an -ism, he should believe in himself. I quote John Lennon, "I don't believe in The Beatles, I just believe in me." Good point there. After all, he was the walrus. I could be the walrus and I'd still have to bum rides off of people.

Ferris Bueller’s Day Off

My service dog, Pico, is a representation of freedom and independence that I might not otherwise have. Being his handler has brought me into a realm of disability advocacy I am grateful for: I am an ambassador for Canine Companions For Independence and an advocate for the estimated 385,000 working service dog teams across the United States.

For the nearly five years I’ve worked with Pico, one of the biggest struggles we’ve encountered is using rideshare services like Uber and Lyft. An estimated 53 percent of the U.S. population has used a ride-hailing platform. Globally, Uber and Lyft complete 16 million rides daily, with Uber taking roughly 70 percent of the market share to Lyft’s 30 percent. Yet for people with disabilities, these platforms are riddled with problems and rooted in a culture of ableism. And as Ferris Bueller reminds us, -isms are not good. To make matters worse, I am not the walrus. and I can’t even pay for rides, much less bum them.

Despite having clearly articulated policies around service animals that mirror federal law, many rideshare service drivers seem to believe the law does not apply to them. Vindicated by their status as independent contractors, they argue, “My car. My rules.” Therein lies the tip of the iceberg surrounding the ableist mindset that the disability community is all too familiar with.

I’d call for a ride, the driver would show, see us both, and inevitably the conversation would begin. “I’m sorry, sir. I can’t take your dog.” I’d politely explain federal law, and most would insist they didn’t care and offer a litany of reasons why they’d be cancelling my ride. I’d be left standing there, forced to repeat the process sometimes two or three times before successfully completing my trip. I’d sometimes build an extra 10-15 minutes of “rejection time” into my travel itinerary. I’d subsequently report these incidents and it quickly escalated into a game of he-said/ she-said. Uber or Lyft would apologize, throw a $10.00 credit my way for the inconvenience and move on. No follow up with me, or to my knowledge, the driver. It would be as if the incident never happened.

But it kept happening. And it happened with such regularity that I began making the painful choice to leave Pico at home. To anyone who relies on a service dog daily, this decision is difficult and never our first choice. To be without our service animals is to be without our medical equipment, which gives us our freedom, independence and our sense of self.

And so on the heels of the death of President George H.W. Bush, the very same president who helped push through the Americans with Disabilities Act, (and who himself had a now famous service dog, Sully), I chose to begin gathering footage of the service denials in the hopes that, with the nation’s eyes focused on the life-changing benefits of service dogs, a sea change might occur.

Since I began documenting my experiences in December 2018 to showcase how widespread disability discrimination is among rideshare platforms, I’ve interacted with drivers whose concerns range from a fear that my pup my will shed uncontrollably (and force them to vacuum) to wondering what to do if he were to suddenly defecate or vomit in their vehicle. I remind them that unlike many of the passengers they will pick up in the early morning hours, Pico is trained and has never had an accident of any kind while working. While minimal shedding is likely, (he is, after all, a 70-pound Labrador Retriever) that’s where reality stops and unfounded beliefs take center stage. And whether it stems from ignorance, fear, or a feeling that they are above the law, drivers are not allowed to deny passengers with service dogs.

Uber’s service animal policy reads in part:

Driver-partners have a legal obligation to provide service to riders with service animals.

A driver-partner CANNOT lawfully deny service to riders with service animals because of allergies, religious objections, or a generalized fear of animals.

By virtue of their written Technology Services Agreement with Uber, all driver-partners using the Driver App have been made aware of their legal obligation to provide service to riders with service animals and have agreed to comply with the law. If a driver-partner refuses to transport a rider with a service animal because of the service animal, the driver-partner is in violation of the law and is in breach of their agreement with Uber.

If you read further, Uber spells out consequences of drivers who violate this policy.

If Uber determines that a driver-partner knowingly refused to transport a rider with a service animal because of the service animal, the driver-partner will be permanently prevented from using the Driver App. Uber shall make this determination in its sole discretion following a review of the incident.

If Uber receives plausible complaints on more than one occasion from riders that a particular driver-partner refused to transport a rider with a service animal, that driver-partner will be permanently prevented from using the Driver App, regardless of the justification offered by the driver-partner.

However, when presented with repeated evidence of a denial of service or a degradation of service wherein the driver makes his disdain for us known on video, Uber routinely chooses the path of least resistance. Their customer service consists almost solely of interactions through the app or a never-ending circle of social media-based robotic responses that urge me to correspond via Direct Message (DM) or by utilizing the in-app support. They claim it is an effort to streamline communication. I believe it is a deliberate effort to keep these conversations hidden and out of public view.

Of the nearly dozen documented instances thus far, only one driver has been confirmed banned from the platform. One driver even went so far as to happily accept us for a short trip, only to fraudulently claim to Uber that Pico had damaged his vehicle so severely as to warrant a $150 “cleaning fee” for something that never happened. They subsequently reversed it, but the fact that it was approved at all raises serious process questions. Recently, when I shared this experience with another driver, he openly and nonchalantly remarked that submitting requests like this was a good idea, and had to be dissuaded from doing so.

In all other instances, Uber has declined follow up when asked what steps they’ve taken as a result of being provided clear evidence in direct violation of federal law and their public policies surrounding consequences, which to me highlights the unfortunate reality that in all likelihood no follow-up actions were taken and the drivers in question were given nothing more than a slap on the wrist, if anything.

The week before Christmas, I sat down with my local FOX affiliate, grateful for the chance to broaden awareness and educate the public. Uber doubled down on their non-response response strategy, issuing a statement that sounded like it had been hastily crafted on the back of a napkin by a public relations team that was seemingly caught unaware, despite my very public broadcasting of these incidents. They said they were “looking into it” and reiterated that their drivers knew they were legally required to follow all federal law and written company policies. If I may paraphrase from Jerry Seinfeld for a moment, “Anybody can have a policy. You just don’t know how to enforce the policy, and that’s really the most important part of the policy, the enforcing. In my frustration at their nonchalant response, I rewrote their statement as if it had come from a place of putting the customer first. A fictional statement admittedly, but the one I myself would have written if, as head of Uber public relations, I had been asked for comment.

Since the FOX piece aired, the majority of engagement on this issue has been largely positive. There remains, however, a faction of the general public not yet persuaded that this issue is even an issue at all. They posit myriad theories about personal motive, my (lack of) knowledge surrounding federal law, and better still, my dogged insistence that Uber and Lyft comply with federal law.

But one essential prong of advocacy is awareness and education, so I want to address some of the recurring arguments I’ve heard since this campaign began.

“There are services for people with wheelchairs. Use them.” Putting aside that we abolished “separate but equal” in 1954, paratransit services (like MetroAcess here in Washington, D.C.) require 24-hour advance booking. While that may work for some, it’s not a viable solution offering the same freedoms afforded to the general public using rideshare. It’s unfair to assume people with disabilities can or should be required to schedule their lives in 24-hour increments. We deserve the same freedoms and flexibilities as our able-bodied counterparts.

Additionally, it is important to clarify that in my case, when I use rideshare, I am completely ambulatory and my wheelchair is not with me. It is not part of the logistical equation and has no impact on the driver whatsoever. That said, Uber and Lyft need to provide easy access to wheelchair accessible vehicles rather than outsourcing to third party vendors completely removed from the on-demand culture on which these companies were built.

“Let Uber/Lyft know you’re traveling with a service dog.” It’s a nice idea in theory, but in practice it doesn’t work. Calling ahead simply invites discrimination without any way to confront it. Particularly on Lyft where users can create a public bio for drivers to see, I tested a theory. In my bio, which includes a picture of me and Pico, I wrote a few lines and self-identify as a service dog handler. Much of the time my rides get cancelled within minutes. The more dubious drivers will see I am traveling with a service dog, drive near my pickup location and sit idle, run out the five minute wait clock, ignore my attempts to call and finally claim I never showed. In the end, I’m left without a ride and stuck with a cancelation fee to reverse and the faint hope that the incident won’t repeat itself when I call a subsequent ride. Think about it this way: Would you call ahead to let your driver know of your ethnicity or sexual orientation in case they had a problem with it? No, because it’s discrimination, and this is no different.

“Some drivers agreed to take you in the end. What’s the big deal?” Yup. In some cases drivers reluctantly agreed to accommodate us following a confrontation or a promise to report them. By then, there had already been a degradation of service. They made their disdain for me and Pico clearly known and that makes for one awkward ride. According to Uber, if after such a confrontation I choose to not complete the ride, they classify that as a denial.

“Use Taxis.” It’s true that taxis are regulated and compliance rates are higher as a result. However, taxis also mean longer wait times, higher fares, no GPS tracking of your vehicle and no guarantee they’ll show. Additionally, there’s also the possibility I’ll need to carry cash if I can’t request a credit card-equipped cab. As someone with fine motor challenges, I try to handle cash as infrequently as possible.

“It’s about money and fame.” This one makes me laugh so hard I have to be extra careful to not fall out of my chair. This is an argument made by able-bodied people who, due to their privilege, forget that the world is made with them in mind. People with disabilities are often thought to be complaining or making a big deal over small issues, when we are simply fighting for the rights the abled community already has and thus takes for granted. Our goal is not to complain. Our goal is to advocate for change and put ourselves out of business, as it were. That starts with raising awareness and hoping we reach critical mass so that the people in positions of power will listen and act accordingly.

People with disabilities constitute 20 percent of the world’s population. And still, rideshare companies like Uber and Lyft behave as though we are a minority undeserving of them instead of the customers keeping them afloat. My hope is that by continuing to document and share my experiences positive change will come in 2019 and we will all be treated with the respect and dignity we deserve.