"The disability community sees disaster looming — more mass death and disablement, and a choice between hospitalization and death, or almost total isolation while everyone else enjoys maskless flying, parties, and eating in restaurants. Meanwhile, individual disabled and chronically ill people increasingly feel like they are now seeing exactly how they will die."

-Andrew Pulrang, Forbes

When the pandemic first began in March 2020, disabled people sounded the alarm. We tried desperately to talk about how deadly and disabling this pandemic would be, and the general response was to dismiss us. We were "othered", told our lives didn’t matter, told not to disrupt your fun and stay over there. As we so often are.

As it became increasingly clear the pandemic would affect the masses, a national emergency was declared. The country, at least for a while effectively shut down. Precautions were taken, and for a brief time it seemed we were all in this together.

Over two years, and 1 million deaths, later it seems the pendulum has swung back toward indifference. The reason so many able-bodied people shout from the rooftops about “learning to live with COVID” is because they very well can. For them, a battle with COVID, particularly if vaccinated, may not prove lethal. For folks like myself with cerebral palsy, which affects the most basic forms of mobility, a potential battle with COVID can go from miserable to life-threatening in a heartbeat.

Cerebral Palsy Alliance Research Foundation USA writes:

“….individuals with cerebral palsy will likely experience trouble quickly. This trouble includes inability to generate sufficient force to clear the airway and in fatiguing with the increased work of breathing.”

An Axios/Ipsos poll this week found just 36 percent of Americans said there was significant risk in returning to their “normal pre-coronavirus life" however, the disability community remains at incredibly high risk from COVID.

With the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shift from deemphasizing infection focusing on risk assessment, the need for more accessible data surrounding infection rates and daily cases remains paramount. At home test kits and personal protective equipment (PPE) need to be more widely available, affordable, and accessible. Perhaps most importantly there needs to be clear indication of the relative safety of public spaces. We need to know what precautions businesses are talking to protect the vulnerable populations they serve.

The pandemic is not over, its impacts are still being seen and felt globally, and the disability community is here to tell you that you are ignoring its current state at your own peril. Every one of you could become one of us at any time. The difference is. when you do, we will welcome you and not cast you aside.

The World Economic Forum

“There is a global disability inequality crisis. And it can’t be fixed by governments and charities alone. It needs the most powerful force on the planet: business.”

— Caroline Casey, Founder, the Valuable 500

Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Accessibility (DEIA) is a topic advocates talk about daily. So much work is happening and yet simultaneously so much work remains. Oftentimes, I think of advocacy the way I think of a book jacket. The material might be the same but different covers may resonate with each member of your audience.

As the World Economic Forum kicks off in Davos this week, I thought it was important to highlight the Valuable 500 Initiative—the largest global network of chief executives committed to disability inclusion. Launched in 2019, the initiative aims to “set a new global standard for workplace equality and disability inclusion by engaging 500 private sector corporations to be the tipping point for change and to unlock the business, social and economic value of the 1.3 billion people living with disabilities across the world.”

Some of the world’s biggest companies including Apple, Microsoft, Google, Sony, and Verizon are among its participants.

Although 90% of companies claim to prioritize diversity, only 4% of businesses are focused on making offerings inclusive of disability according to the World Economic Forum.

A May 2022 report published by the Valuable 500 also found that:

• 33% companies surveyed have not developed or begun to implement a digital focus on accessibility

• 29% of companies have a targeted network of disabled consumers or stakeholders.

The cost of excluding people with disabilities represents up to 7% of GDP in some countries. With 28% higher revenue, double net income, 30% higher profit margins, and strong next generation talent acquisition and retention, a disability-inclusive business strategy promises a significant return on investment.

On the federal level, data on inclusion efforts tells a similarly disheartening story. A newly released report by the EEOC found that persons with disabilities remain heavily underrepresented in leadership positions; 10.7% of disabled employees are in positions of leadership vs 16.4% for those without. Further, the report noted that people with disabilities were 53% more likely to involuntarily leave federal service than persons without disabilities.

Clearly, both privately and publicly, a lot of DEIA work remains. These disconnects in the data further support the need for advocacy around not only things like Global Accessibility Awareness Day, but also an increase in disability representation to effectively close these gaps.

Let disabled people not simply have a seat at the table, but a voice in the conversation. Your company will be better off for it.

Global Accessibility Awareness Day

"The truth of the matter is, Netflix Director of Product Accessibility Heather Dowdy explained, the disability community “has been here all along.” As such, it makes sense to want to normalize and tell their stories. Indeed, the pandemic has only reemphasized the importance of accessibility and assistive technologies."

Forbes, Steven Aquino

-

Today we celebrate Global Accessibility Awareness Day, highlighting the advances making technology and entertainment more accessible to the disability community. Oftentimes, seen as an afterthought, these enhancements are vital to ensuring disabled people can participate equitably as consumers of entertainment as well as fully leverage a company’s complete product line readily and with full confidence their needs will be met.

The disability community accounts for 20% of the global population, the largest underserved minority. When you consider accessibility for one, you enable it for all. So many of the tools and technologies in wide use today were initially developed for disabled people, and yet are seen as ubiquitous today. Think captions, speech to text, or screen adjustments on mobile devices.

In recent days companies like Apple, and Microsoft have rolled out enhancements to their product lines aimed at people with disabilities. Apple, for example unveiled Door Detection, helping those with vision impairments more easily navigate their surroundings. Additionally, they’ve improved functionality of the Apple Watch allowing it to be controlled through the iPhone; a larger screen with more real estate that also allows users the benefit of assistive technology already present within iOS— features like voiceover and magnification— not yet independently available on Apple watch.

For its part, Microsoft announced Thursday in a company blog post recent improvements included in Windows 11 that aim to make its OS more accessible, including Live Captions and new natural voices for users of screen readers. Last week at its annual Microsoft Accessibility Summit, a slew of adaptive technology for computing and gaming was also unveiled. Additionally, Microsoft touted its recruitment efforts to improve disability representation within the company.

A new study from Microsoft Education found that 84% of teachers say it’s impossible to achieve equity in education without accessible learning tools. And 87% agree that accessible technology can help not only level the playing field for students with disabilities but also generate insights that help teachers better understand and support all their students.

Accessibility benefits everyone. While companies like Netflix, Apple, and Microsoft are to be applauded for their progress, they represent merely a step forward in equity. We must continue to push all companies, regardless of overall size, or market share to fully embrace equality for all. To that end, I look forward to the day when Global Accessibility Awareness Day ceases to exist and it fades into the background.

Madison Cawthorn

The disability community talks frequently about how representation matters, and it does, especially in Congress where that representation can lead to better lives for disabled people. Senator Tammy Duckworth of Illinois is a perfect example of the positive representation we need more of, routinely uplifting our community and showing what is possible through advocacy.

The flip side is recently unseated Representative Madison Cawthorn (NC 11) who is the worst thing to happen to disability representation since the rise of toxic positivity. Not only did his openly ableist views harm the disability rights movement, he actively found ways to misrepresent what it looks like to move through the world as a disabled person.

When we say representation matters, it does. Madison Cawthorn's re-election loss however is a positive step forward for disability rights.

Finally, congratulations to my friend Kristen Parisi whose reporting on Representative Cawthorn was recently featured on Jon Oliver's Last Week Tonight on HBO Max.

Over 3.5 Billion People Will Need Assistive Products by 2050: Report

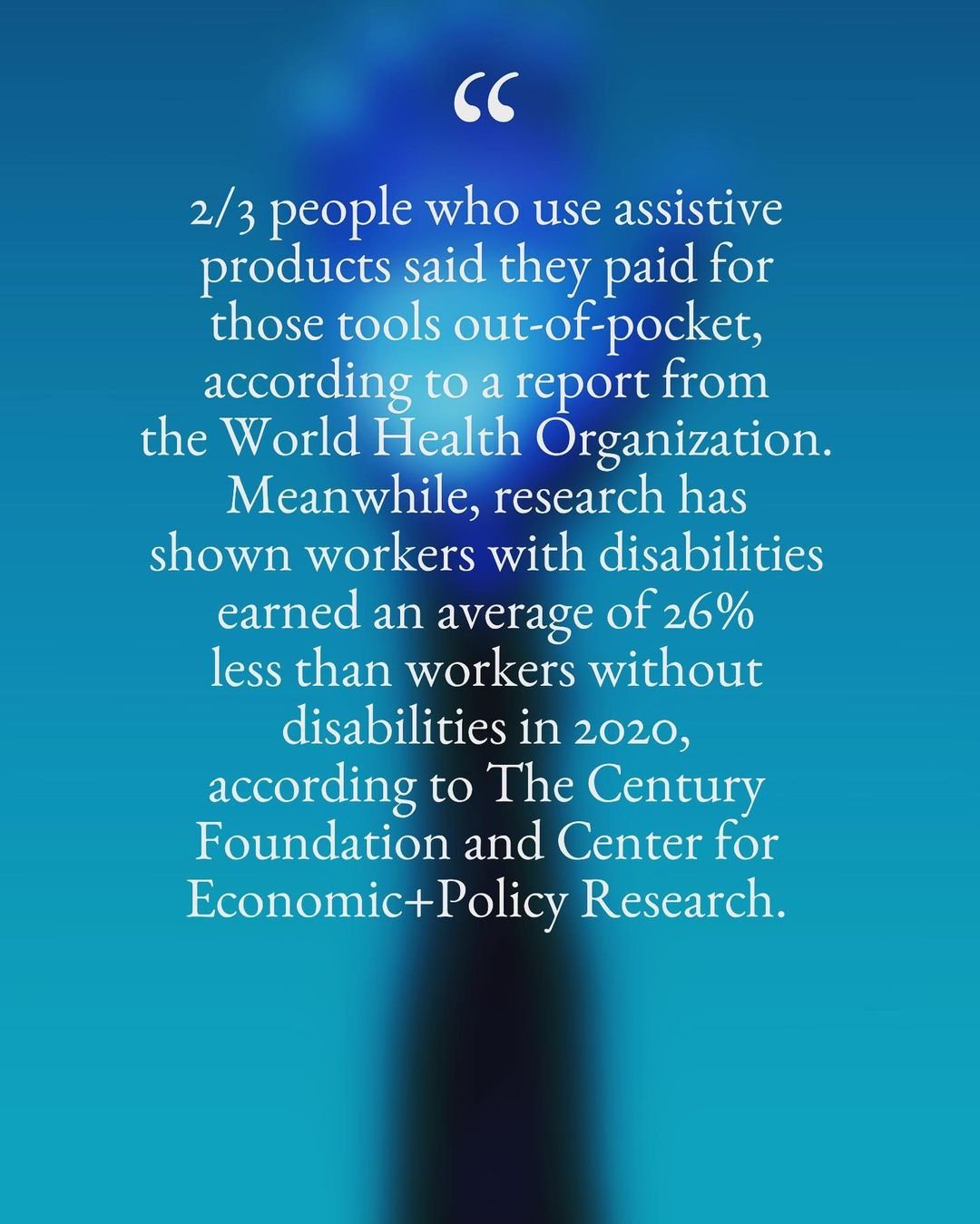

About two in three people who use assistive products said they paid for those tools out-of-pocket, according to a report from the World Health Organization. Meanwhile, research has shown workers with disabilities earned an average of 26 percent less than workers without disabilities in 2020, according to The Century Foundation and Center for Economic and Policy Research.

While some assistive tools are easily available, Maria Town, the president and CEO of AAPD Foundation said more "specialized" products can be "very costly," even if the individual in need has public or private health insurance.

Meghan Roos, Newsweek

I count myself among the 2.5 billion people who currently use assistive technology daily. Often, this is technology paid for out of my own pocket.

My wheelchair, leverages assistive technology in the form of power assist wheels. This technology enables me to move more freely and easily through different terrain without putting undue stress on my body in numerous ways; especially while working with Canine Companions® Pico as we navigate a major city with hills and distinct types of terrain. While insurance did cover some of this, a significant percentage came out-of-pocket. Without this technology I would not be able to navigate my life safely and easily. It has provided a freedom and flexibility that I would otherwise not have.

For years, I struggled with typing; causing strain and stress on my hands, fingers, and even eyesight. While I can effectively use voice dictation today and can attest to how much it has streamlined my workflow and saved me undue physical stress, the startup costs were innumerable.

For many people with disabilities, assistive technology is not a luxury, it is not a “nice to have,” nor is it something to ogle over and think about how cool it would be if you had it. It is what enables us to participate freely and easily in society that is not built with us in mind. We use this technology to level the playing field. However, it can and does often come at significant cost. Colloquially referred to within the disability community as the “Crip Tax,” it is the cost-of-living increase as a consequence of living life as a disabled person.

That is just one of the many reasons why equal wages are so important for everybody. Disabled people earn seventy-four cents on the dollar compared to our nondisabled colleagues. This is why, in every industry, every profession, and every company, representation matters. Disabled people need support from leadership not only so we can thrive at work with a supportive team that understands and appreciates our needs for assistive technology, but further so we can advance our careers on-par with our nondisabled colleagues and close the wage gap.

For us it is the difference between inclusion and exclusion, feeling seen, or feeling ostracized. Feeling validated or cast aside.

Over 3.5 Billion People Will Need Assistive Products by 2050: Report

Some Minority Workers, Tired of Workplace Slights, Say They Prefer Staying Remote

“People with disabilities have been left out of civic life for so long,” Carol Glazer, president of the National Organization on Disability says, “If we don’t see them in our schools, in our communities, in our workplaces, it only reinforces a lack of understanding and the implicit bias that leads to microaggressions.”

Alex Janin, The Wall Street Journal

As companies encourage a return to the office, it is important to remember that people with disabilities are at risk for being left out of the conversation. Many are still unable to safely engage in an office environment for medical reasons. The pandemic helped normalize work from home protocols and accommodations which were previously a struggle. Now, with those same accommodations seemingly rolling backward in favor of a return to “normalcy” many are having to choose between their health and safety and workplace visibility, effectively risking becoming second-class citizens in their own jobs.

There have been numerous times in my own career where an office environment was not always the most welcoming. I’ve often dealt with disparaging comments, micro-aggressions, and the all too often unsolicited advice/commentary that accompanies being disabled. Non-disabled colleagues often feel they have a right to not only to our medical history but to freely dispense advice about how to handle it. It is not only demeaning, but presumptuous, and extremely harmful. As a near daily occurrence, this can be exhausting. Most non-disabled folks wouldn’t think twice about preserving the privacy around most other discussions concerning health, yet disability seems to be its own designated category, unworthy of such discretion and privacy.

An office environment certainly does have its place and benefits when it comes to fostering collaboration. I am all for those things and support them when they can be done safely for all. But we are not there yet. We have also demonstrated over the course of the pandemic that many disabled employees benefit from accommodations and that no workplace hardship is created in doing so.

We should not be penalizing anybody (directly or otherwise) who chooses to work from home for the safety of their own mental and physical health.

Some Minority Workers, Tired of Workplace Slights, Say They Prefer Staying Remote

Disability Bias in AI Hiring Tools Targeted in US Guidance

As many as 83% of employers, and as many as 90% among Fortune 500 companies, are using some form of automated tools to screen or rank candidates for hiring, according to EEOC’s Charlotte Burrows.

-Bloomberg Law

With the rise of AI tools in recruiting, new guidance issued by both EEOC and U.S. Department of Justice is welcome news. Disability advocates have long known that while these tools can be useful for the employer, they can raise questions around bias that violate the ADA, including the use of personality tests with non-job specific questions, camera sensors, or timed tasks that don’t easily allow for reasonable accommodation.

This guidance also comes after U.S. Department of Commerce appointed 27 experts last April to the National AI Advisory Comittee.

The disability community already faces tremendous hurdles in hiring discrimination, in large part due to employers outdated views on what people with various disabilities bring to the table.

While AI can be a useful tool, and can certainly provide valuable insight, the hiring process needs more human connection and understanding across the board, not less, especially around disabled candidates.

New PSA Urges More Disability Visibility and Representation in Hollywood

“A [2021] report on the television writing from the Think Tank for Inclusion and Equity found that 93% of disabled writers surveyed said they were the only disabled person on staff, and 97% of writing rooms had no upper-level disabled writers.”

-Marc Malkin Variety

Think about that for a moment. Disabled people are massively underrepresented in entertainment. And we are as diverse as we are numerous, accounting for 20% of the global population. Over the last few years disabled people have slowly begun to see themselves in newer series, movies, and television.

While representation has certainly improved, all too often it’s done as a trope, or an act of tokenism that actually causes more harm than good. That’s why diversity in writing rooms and elsewhere in Hollywood is as vital as inclusion, equity, and accessibility itself. Each of these pieces work together and can not stand alone. We need not just representation of disability, but we need it across the spectrum to account for the depth, breadth, and power of the disability experience.

Thank you to Inevitable Foundation for your important work.

New PSA Urges More Disability Visibility and Representation in Hollywood

When Your Wheelchair is Your Legs: Holding Airlines Accountable For Broken Mobility Equipment

Travel these days gives me a bit more anxiety than it used to. It’s never easy, as I wrote about years ago, and a lot has changed. There’s my usual luggage, and my service dog, Pico. He is truly a joy to fly with as he rests at my feet and naps for the entire flight. There’s my custom-fit wheelchair with power-assist wheels, which took 18 months to obtain through insurance and still left me with several thousand dollars in out-of-pocket costs. Expensive? Sure. However, it’s a small price to pay for independence. So understandably, when I travel, there’s added stress when it comes to the treatment of my wheels by the airline. There are things we can do as wheelchair users to reduce the likelihood of damage, but as with anything in life, there are no guarantees. Traveling is especially stressful for wheelchair users. It’s why many of us avoid flying altogether.

As a wheelchair user, I’m entrusting an airline with the very thing that enables me to move freely throughout my day. Once I’m at the gate, I hope all my carefully articulated instructions are followed and that my chair is handled appropriately. I know some people who are nervous flyers. If they are religious, some will cross themselves to ensure a safe landing. The entire time I’m flying I’m wondering, “Will my ‘legs’ work when we land?” There isn’t enough in-flight entertainment to quell that fear.

When disability advocate and writer Kristen Parisi shared with me her tale of airline travel hell, I was saddened but not surprised. “We landed, and they didn’t know where my chair was,” she recalls. “There was no apology, no acknowledgement of how I must be feeling in this moment. They were more focused on getting me off the plane so the crew could go home. Airlines don’t care. They treat our chairs like they are pieces of luggage. Those are my limbs. I need them to survive and they treat it like trash.”

Parisi reflected that disabled people “are constantly forced to be advocates because society would rather just brush us off and not just deal with it. On the days when you’re just trying to have a vacation you still have to be a constant advocate for yourself.”

While the airline did eventually reunite Parisi with her chair after a two hour delay, data shows it’s a far too common occurrence for wheelchair users. Airlines don’t have the greatest track record with mobility equipment. The only reason we knew this is thanks to Senator Duckworth’s own experience, leading to legislation requiring airlines to report on the frequency of these incidents. (This is yet another reason why representation of disability matters, especially in Congress.)

From January to March 2021, Delta Air Lines handled 15,547 wheelchairs and scooters and reportedly mishandled 103 of those, according to the Air Travel Consumer report. Major airlines combined mishandled 712 or 1.19 percent during that same period, which roughly equates to 23 daily instances where a wheelchair user’s mobility equipment sustained damage. That number may seem small, but it’s still too many. If that many animals were dying as a result of negligence there would be an uproar.

Imagine the airline breaking your legs and saying, “We’re sorry. In the meantime, let’s send you to the hospital and we can fight over the bill later!” That’s essentially what happens when a wheelchair is lost or damaged. It’s not supposed to be that hard, but it is. They’re required by law to cover the cost of damage, repair, or replacement but it’s never that simple in practice.

Our mobility equipment is as unique as we are. Rentals aren’t always feasible and repairs take days, weeks, or months. Suddenly that trip you had planned isn’t happening and you’re stuck in a hotel room unable to move. It’s also likely that airlines are underreporting the actual amount of damage that occurs. The process of filing the multiple reports and providing documentation with persistent follow up can be exhausting, and the last thing any wheelchair user wants on top of damaged equipment is added stress. If your legs are broken, your first thought is dealing with the pain, not bureaucracy. When overwhelm kicks in and you’ve got limited time to follow a regimented process it can be anxiety producing, and with an inability to move, literally paralyzing.

Travel has never been easy for anyone, even prior to the pandemic. As we work to establish our new normal, new stressors are par for the course as we learn to navigate them. There is a lot about the future of travel that remains uncertain. One thing remains clear, however. As thoughts about travel begin to reenter the minds of travelers with mobility equipment, the anxiety that comes with our travel isn’t going anywhere. We need to continue raising awareness, making noise, and holding airlines accountable for their mishandling of our equipment. Travel can bring with it tremendous freedom and joy, provided that nobody takes our ‘legs’ out from under us when we land, but we still have a long way to go.

The Pandemic Created A Systemic Shift For Disability Rights and Accessible Space, Even If It Was Accidental

For the past 18 months or so during the pandemic, time stood somewhat still. Normal routines shifted or changed while still others fell off entirely. One that I missed deeply was my daily Starbucks run. Yes, they quickly adapted and offered drive up or curbside options, but it wasn’t until recently that I began slowly reemerging from isolation, back to Starbucks, and into the newly established normal.

I admit my anxiety about reemergence is high. I routinely find myself asking what a post-pandemic world will look like. Will the lessons surrounding the normalization of telework remain? What about telehealth and virtual appointments? Will disabled people who were shamed for using grocery delivery or reliance on food delivery apps finally feel free of judgement since they’ve now become commonplace? And what will going out into the world look and feel like as a wheelchair user with a service dog in public space? Everything feels so uncertain.

On my daily walk with my service dog, Sir Pico, I passed my local Starbucks and heard the familiar Siren song calling to me. “Go in. It’s been 18 months. Go in. You’re vaccinated. You’re masked. It’s okay. You deserve it. Maybe grab some avocado toast while you’re at it, you entitled millennial.” (My inner critic really needs to shut up.) It was part reassuring myself, and part feeling like my addiction grabbed me full-on by the shoulders and was shoving me toward the door.

I went in. From a disability perspective, what I saw was glorious. The Choir of Heavenly Angels sang in my head. OK, so it wasn’t that dramatic, but what I saw was open space and inclusive design that didn’t exist prior to the pandemic. Social distancing meant no narrow rope lines with customers standing shoulder-to-shoulder. The tables that once presented themselves like a navigational maze with potential death traps not dissimilar to the game Frogger, were gone. And customers weren’t packed wall-to-wall in every corner waiting for their drinks to be made while I, at my lowered height uttered “Excuse me, sorry about that.” I no longer had to navigate between random display items—constant reminders that the world is seldom built with disabled people in mind.

Instead, there was openness. I rolled in, and for the first time entered a public space that I felt gave me room to breathe. I had the ability to unapologetically be myself, to exist, and not feel like I took up too much space or was somehow unwelcome just by virtue of being me. I grabbed my drink which I had preordered on the app, thanked the barista, turned around, wheeled outside, and sat at the table contently sipping my Mocha Frappuccino, having felt seen for the first time in a long while as a disabled person.

If this seems like a simple moment to you, or perhaps like I’m getting too excited about an everyday event, that’s because I am. Not because I went outside and lived my life or because I’m vaccinated and the world is slowly opening. It’s because the pandemic has forced us all—especially businesses—to redefine what “normal” truly looks like. Prior to the pandemic, the disability community was routinely told that what we needed was “special,” or costs too much, or couldn’t be done because it created an organizational burden. But the pandemic proved all those obstacles were accepted simply because non-disabled people hadn’t yet felt the imperative to act beyond their own self-interest. For far too long the disability community felt excluded in spaces simply because they weren’t built for us. COVID thrusted upon the non-disabled a new lens through which to see the world, getting their attention in a way our screaming, yelling, and pleading could not; because they finally, for once, saw themselves in us.

As a disabled man, I could not be more elated by the possibility that open space is the new normal. As short as our collective memories may be, I’m hopeful that at least this one lesson about accessible spaces sticks. The disabled community will continue to fight for more access and more inclusivity, but for right now, in this moment, I’m going to take the win for this unintended result of COVID. I wish it hadn’t taken a pandemic to get here, but I’m ready to enjoy the wide open space.